Yorktown is one of the three colonial towns that make up the “historic triangle” area of Virginia, along with Jamestown and Williamsburg. The same deep water features that made it a bustling port city also made it a perfect location for Lord Cornwallis to choose for a British naval base during the American Revolution.

Yorktown is famous as the town where the Colonists clinched their win in the Revolution. A visit to Yorktown should include a stop at the Battlefield, historic main street of Yorktown and the Museum.

It sustained more damage during the American Civil War, and there are sites related to that conflict as well you can visit at Yorktown.

Getting There

Location: South-East coast of Virginia

Transport:

Nearest major airports are Norfolk, VA (ORF – 50 miles) or Richmond, VA (RIC – 45 miles)

You really need a car to see the Yorktown Battlefield sites. The National Park Service has a fantastic self-guided driving tour and complimentary app for smartphones.

Already have a good idea of the history of Yorktown? Then bypass the history lesson and Skip to the Trip!

Your Visit to Yorktown Starts in 1691

By the end of the 17th century, the English had been settled in the area for nearly 100 years after establishing Jamestown in 1607. Yorktown was founded in 1691 and was named after King James I’s son the Duke of York.

Jamestown is only about 20 miles to the west of Yorktown but harder to access from the ocean by river. The influence of Jamestown was starting to wane by 1690 and towns like Yorktown were the new up and coming port cities. You can learn more about the history of Jamestown on this trip.

Virginia’s economy was booming due to the tobacco trade, which led to the establishment of slavery in the United States. By 1750 there were more than 1,800 people living in Yorktown – which is nearly twice the size of my hometown today!

As a colonial port, Yorktown was responsible for collecting taxes on imports, inspecting cargo and recording items being shipped.

Prelude to War

The English had been fighting the French in Europe on and off for hundreds of years over a number of issues. So when the Seven Years War (known in North America as the French & Indian War) broke out between Colonial nations around the world, it was no surprise the American colonies would become a battleground in 1754.

England won that war (with help from Prussia), and they expected the colonies to pay for the support and protection that had been provided by the British government.

This led to a series of taxes in the 1760’s imposed on the colonies such as the Stamp Act, the Sugar Act and others known collectively as the Townshend Acts, named after the man largely responsible for their design, politician Charles Townshend.

The colonists didn’t necessarily disagree with the taxes but they did resent that the distant British government, and not their locally elected officials, were the ones determining and imposing them.

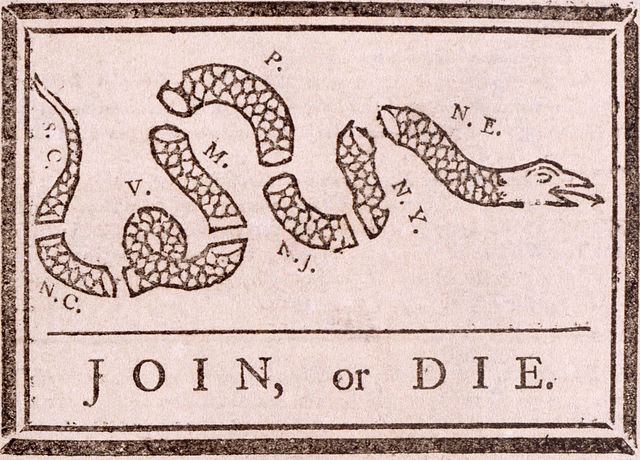

Resentment and tensions continued to grow. Confrontations throughout the colonies gave rise to events like the Boston Massacre in 1770 and the Boston Tea Party in 1773. Yorktown also had a Tea Party in 1774 when they dumped tea in Yorktown Harbor to protest British tea taxes.

The Revolutionary War begins with Lexington & Concord in April of 1775. By 1776 the Declaration of Independence is signed and support for the Revolution grows.

Yorktown & the Revolutionary War

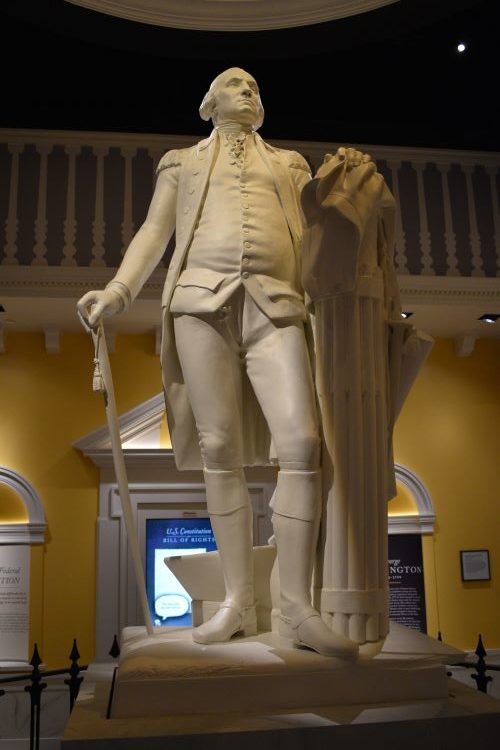

Following some significant losses early in the Revolutionary War, General George Washington essentially adopted a strategy of attrition. He hoped to wear down the British to a point where it was no longer worth the effort to keep fighting the colonies.

This was no small task for the Americans, who didn’t have much food, clothing or supplies. We received significant support from France, happy to cut the English down a notch.

By 1780, the British forces were split between General Clinton in the North, based out of New York, and Lord Cornwallis in the south. Cornwallis had already captured Savannah and Charleston when he was ordered to establish a deep water port in Virginia.

Yorktown was selected as the site for the port, and its place in history was secured.

The Battle of Yorktown: 1781

Washington joined up with French commander Comte de Rochambeau once the French army landed in Newport, Rhode Island. Together, the forces marched to Virginia. Meanwhile, a French fleet was en route from the West Indies to provide support by sea.

In order to fool the British into thinking the attack would be against Clinton in New York, Washington ordered army camps and large bread ovens to be built in view of New York City in order to give the appearance of preparing for a long siege. He also drafted papers discussing an attack on Clinton that were allowed to fall into British hands. Sneaky!

Meanwhile in Yorktown, Cornwallis had been fortifying the harbor.

The French fleet arrived in early September and a naval battle ensued. Many British ships were damaged in the battle, and had to sail up to New York for repairs. The French navy remained behind and set up a blockade to prevent their return once repaired.

Cornwallis had over 8,000 troops in Yorktown. The American and French forces, however, numbered more than twice as many, with 17,600 soldiers.

Cornwallis had been corresponding with Clinton in New York and thought reinforcements would arrive before too long. But reinforcements never arrived.

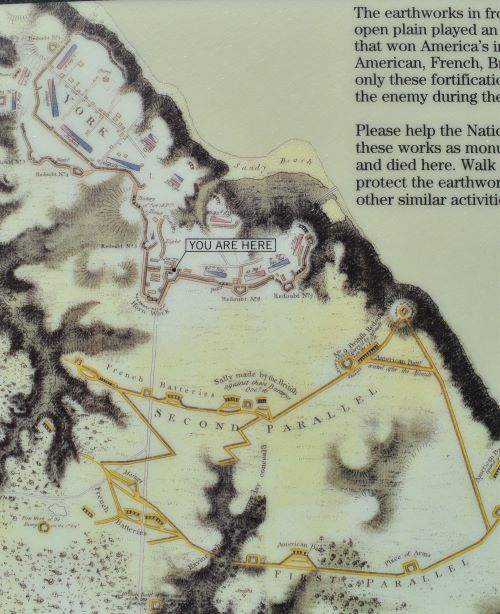

Cornwallis had his men pivot from fortifying the harbor to fortifying their position at Yorktown. Ten redoubts (small earthenwork forts) were dug around the town, connected by trenches and protected by heavy artillery.

The Americans and French dug their own lines as well and the siege of Yorktown began.

Under near-constant fire, the Allied forces knocked out most of the British artillery by early October. Cornwallis also got the unfortunate news that his reinforcements from Clinton were delayed again. Cornwallis attempts to escape across the river but a sudden storm erupts and very few were able to escape.

The allies dug a second line only 400 yards from the British lines. Artillery was moved up to the new line, but the trench could not be completed without capturing British redoubts 9 & 10.

The Code Word is "Rochambeau"!

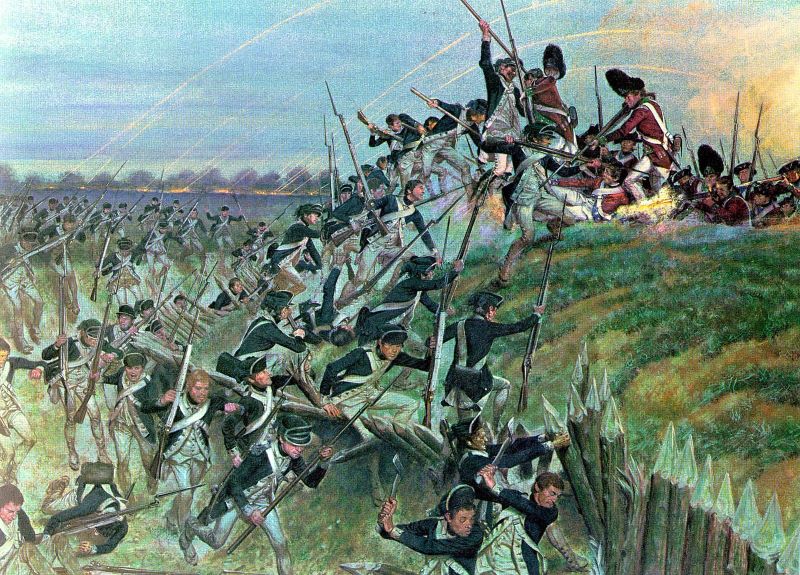

The French forces were tasked to attack British redoubt #9 and Alexander Hamilton was in charge of securing redoubt #10. Fans of the musical “Hamilton” will recognize the line from the song “Yorktown” – “The code word is ‘Rochambeau’, dig me?”

In order to take the British by surprise, the soliders were instructed to unload their guns and fix bayonets. The surprise charge worked and in less than 30 minutes both sections were captured.

Cornwallis Surrenders

Surrounded by troops on land and blockaded by water preventing escape by boat, Cornwallis finally sent a British drummer out with a white flag to lead one of his officers to surrender.

On October 18, 1781, four officers representing the armies met at the Moore House nearby to negotiate terms of the surrender. On October 19, Cornwallis led his troops out of Yorktown, flanked by American troops on one side and French on the other in a row that stretched out more than a mile. They laid down their arms in a nearby field as part of the terms of surrender.

Also conveyed in the musical “Hamilton“, British troops are believed to have marched to the tune of “The World Turned Upside Down“, a British song popular at the time which recounts events that are too unbelievable to be true. It’s a pretty jaunty tune, which you can hear the US Air Force Band play here, but the sentiment of the song had to pretty accurately reflect the shock the British felt from having lost such a significant Battle of the War.

The Loss at Yorktown Finally Ends the War

Following the surrender at Yorktown, the British still had 26,000 troops in North America, but the resolve to keep fighting was significantly diminshed. By this time, the British were fighting in India, Ireland, the West Indies and elsewhere. Washington’s strategy of attrition had worked.

In March 1782, the British Parliament passed a resolution saying the British should not continue the war in America. Later in 1782, British and American delegates drafted articles of peace and in 1783 the Treaty of Paris was signed, finally ending the war and acknowledging American independence.

Yorktown After the Revolution

The cost of having such a significant role in American history was high. Much of Yorktown was destroyed in the War. Recovery was slow, and Yorktown remained rural and agricultural.

Yorktown played a role again in the Civil War, when Confederate troops selected the site as their Headquarters for operations in the area. The Union army wasn’t far behind, but the fighting took place nearby, at the Battle of Williamsburg in 1862. The Union Army won that battle, and moved into Yorktown until General Grant abandoned the town in 1864.

Following emancipation of the slaves as a result of the Civil War, the agricultural plantation system that had been in place previously was no longer tenable. Replaced by smaller farms, grain remained a main staple, but crops like potatoes, sorghum and peanuts also were grown.

In the 20th century, industry and military development began to overtake the farmland. You can see this today with the Naval activity in nearby Newport and the NASA Research Center at Langley in Hampton.

What to See When You Visit Yorktown

There are two self-guided driving routes to follow. The red arrows take you in a circular route to Battlefield sights. Trenches and earthenwork forts have been rebuilt and artillery added to show what it would have looked like at the time of the siege. The yellow route takes you to the Allied Encampment locations and the only remaining original redoubt left from the war.

Each route is about a 45 minute drive but there are places to pull over and explore at each stop. The encampment tour doesn’t have as much to see since the fields have mostly grown over and no buildings or artillery remain. I drove the route in about an hour only stopping a few times along the way. The red tour had much more to explore and took me almost 3 hours to complete!

Start at the Yorktown Battlefield Visitor Center for your route pass and map. There’s also a Yorktown tour guide app that has the map and audio commentary to listen to at each stop. It definitely added more depth to the visit!

I also found an excellent Podcast series called “Key Battles of the Revolutionary War” that has a great episode on Yorktown. This 30 minute episode is great supplemental commentary to the NPS app.

In order for the second siege line to be successful, it needed to extend to the river. Two British redoubts were in the way: #9 & #10. The French were tasked with taking Redoubt 9 and the Americans, led by Alexander Hamilton, took Redoubt 10. Each group achieved their directive, further supporting an Allied victory.

Fourteen Articles of Capitulation decreed the terms of the surrender. British troops would be considered prisoners of war and dispersed throughout the colonies to wait out the end of the war.

Weapons and artillery were also surrendered, and as the troops marched out of Yorktown they were directed to a field to lay down their arms. “Surrender Field” is another stop on the driving tour.

The Yellow tour takes you to several American and French Encampent sites. You can see where Washington had his headquarters, a French Artillery Park and a French Cemetery.

My favorite part of the Encampment Tour was the untouched British redoubt that was part of the British outer defense line. This redoubt was abandoned by Cornwallis the day after Washington and Rochambeau arrived. It’s pretty much been left to sit since then.

This is an excellent museum that covers the lead-up to the Revolution, through key battles, and the aftermath. There is an outdoor living museum area here with a Colonial encampment set up in a Virginian farm setting. Historical interpreters rotate through different stations and you can learn about life as a soldier in the camp.

Don’t miss the 9 minute 4D film “The Siege of Yorktown” – complete with visual effects and a 180-degree screen for a fun immersive experience.

The museum has a number of neat artefacts from the pre-Revolutionary period. One of my favorites was a ceramic mug with an image of the Prime Minister William Pitt (“The Elder”; his son William was also PM later).

Pitt led the colonies to victory in the Seven Years’ (French & Indian) War and reportedly said “I rejoice that America has resisted” to the Stamp Act.

Pitt tried to find a compromise for the Colonies in America, and supported many of the policies the colonists were asking for: consent to taxation, an independent judiciary with trial by jury (the colonies were subject to military courts by this time) and the establishment of an American Continental Congress.

By this time, however, England had defeated two major powers, France and Spain, in the Americas and the sentiment ran high that they could tame the upstart colonists as well.

Pitt’s views garnered much support for him in the colonies initially, and I think it’s neat that he was memorialized on a mug. He was not in favor of total independence, however. In 1778 he stood to argue against independence for the colonies and had a heart attack and died.

Outside is the living history portion of the museum with a replica army camp set on a Virginian farm. Historic interpreters are around to tell you all about life in the camp as a solider, or the farmer that owned the land, or as a family member of the soldiers who often traveled with the group if they were unable to stay in their homes!

The farm portion of the living museum had crops growing, tobacco drying and several interpreters on hand to describe life in colonial Virginia. I asked one of them how you were supposed to get linen from flax and they let me go behind the rope to thrash, scrape and comb the fibers. What you end up with is a really soft, fine fiber that is almost silken! It was really neat to give it a try. I didn’t spin the fibers into thread, but the interpreter had me roll it in my hands to simulate a spinning wheel and I came away with a pretty neat souvenir of my hard work!

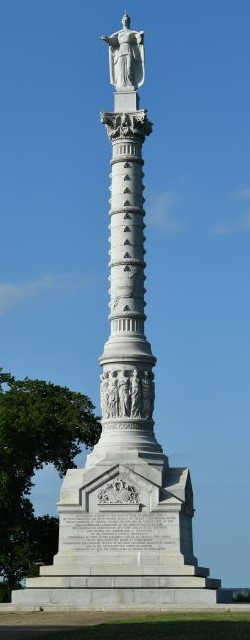

Calls to commemorate the American (and French) victory over the British came quickly after the battle – even before the end of the war! The Continental Congress resolved to built a monument at Yorktown in 1781 though it was not actually built until 1884.

The memorial is a granite column topped with a statue of Liberty, standing 98 feet tall. The base includes a dedication of the monument as a memorial to the victory, a narrative of the Siege, the alliance with France and the treaty with England.

Thirteen female figures ring the base of the column standing arm in arm. They represent the unity of the 13 colonies.

The historic Main Street of Yorktown has been preserved as much as possible – most of the town was destroyed in the war. The National Park services has done a nice job restoring buildings, so there are a dozen or so to see along the short walk. The road is closed to automobile traffic during the day, so it makes for a nice walk. The historic district is only a block up from the waterfront, so you can park in one spot and walk to the other fairly easily.

One building, the Cole Digges house, has been converted to a coffee roastery. I stopped here for an iced coffee and to poke around the building a bit. There’s seating upstairs and outside and the coffee is delicious! They had just roasted a batch the morning I went and the place smelled amazing.

The Digges family were wealthy tobacco merchants at the turn of the 18th century and the home was built around 1720. Cole Digges was born in 1691, the same year Yorktown was founded and he lived through its heyday.

His son, Dudley Diggs, also has a home nearby. Dudley’s home was built around 1760 and is one of the few structures which still has its original colonial framing. The timbers show damage from the artillery fire it was subjected to, but it survived the siege. Following the battle, Yorktown’s prosperity and economy declined.

I’m glad this was marked or else I wouldn’t have realized what it was. The “Great Valley” was the thoroughfare the colonists used to move between the waterfront and the businesses and government offices on Main Street.

The waterfront area of Yorktown has a dozen or so shops and restaurants worth a stroll. Plan accordingly, though. When I went in June nearly everything was closing up by 5 or 6pm! It was surprising because there is a really nice beach right there with lots of people, so I would think at least the restaurants would have stayed open later.

Touring these sites on a visit to Yorktown will give you the full picture of how the town grew and declined within the span of a century. The town played a critical role in our history then quickly faded into a quiet town, which is partly why there is still so much preserved for our benefit today. It is a definite time travel adventure!

Check the reading list for recommendations. A couple of books I liked on this period were “Almost A Miracle” & “Early America”.

Got some extra time to spend in the area? Check out this trip to Jamestown for even more colonial history!

Post Sources:

Visit Yorktown website. Accessed 19 June 2021. Yorktown Battlefield website. National Park Service. Accessed 19 June 2021. York County VA website. Historic Resources. Accessed 19 June 2021.